Fibronit

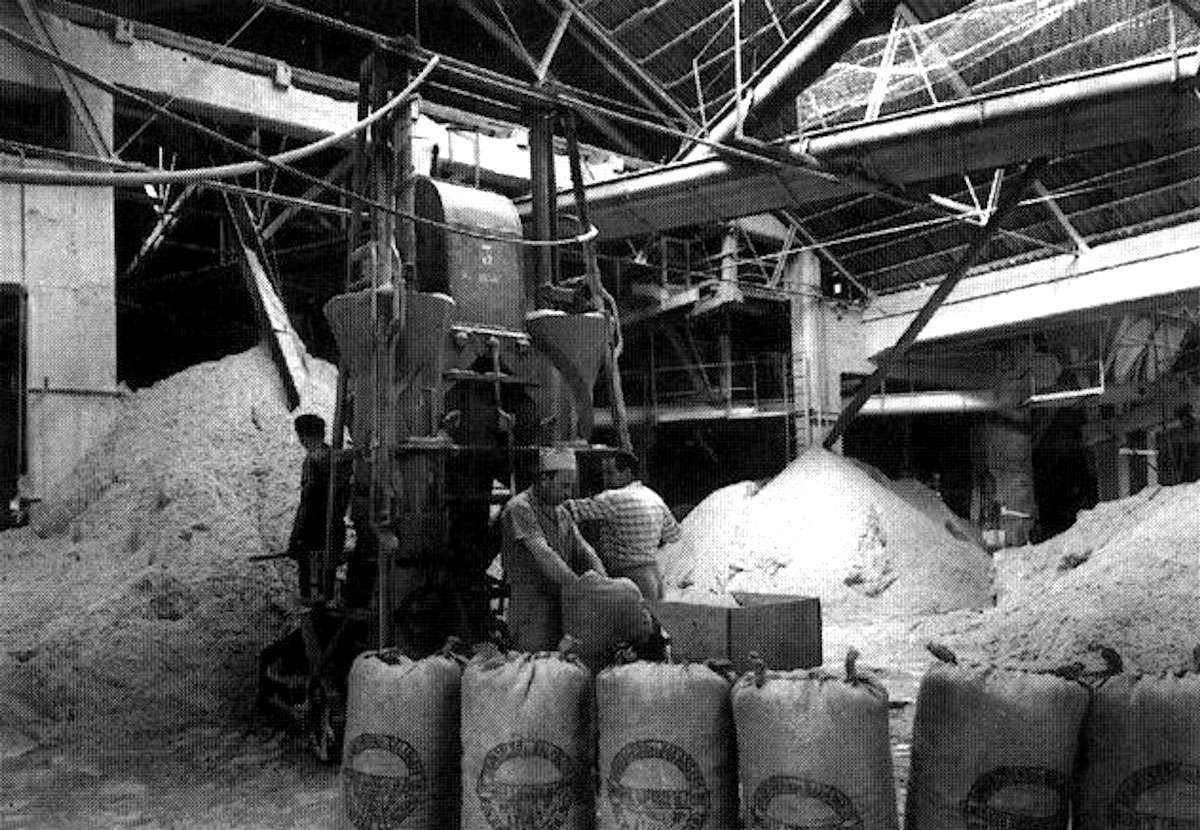

→ The manufacture of the artifacts was done by hand and mainly included flat and corrugated slabs, flues, tanks, sleeves, ducts.

The asbestos was transported in jute bags, then shredded and reduced to powder (milling). Later the fibers were mixed with cement and kneaded with water, then shaped. Finally, after the seasoning, the artifacts underwent a further grinding on the lathe. The recovery of the jute bags was done manually through “dusting”, obtained by banging the bags against the walls.

In 1946 a second department was opened, that of “special items“; later, at the end of the fifties, the pipe production department came into operation.

HISTORY

The Fibronit industrial complex, owned by the Cementifera joint-stock company of the same name, was built in Bari in 1935, on an area of 100,000 square meters, at the crossroads of what would become three districts with a strong identity for the city of Bari: Madonnella, Japigia and San Pasquale.

The factory, in which about four hundred workers were employed, produced items for the fiber cement construction, a compound of cement and asbestos better known as eternit, from the name of the company that had patented and registered it as a trademark. Known for its heat-resistance and flexibility properties, as well as its sound-absorbing characteristics, this material found increasingly widespread use in the post-war and economic boom years. →

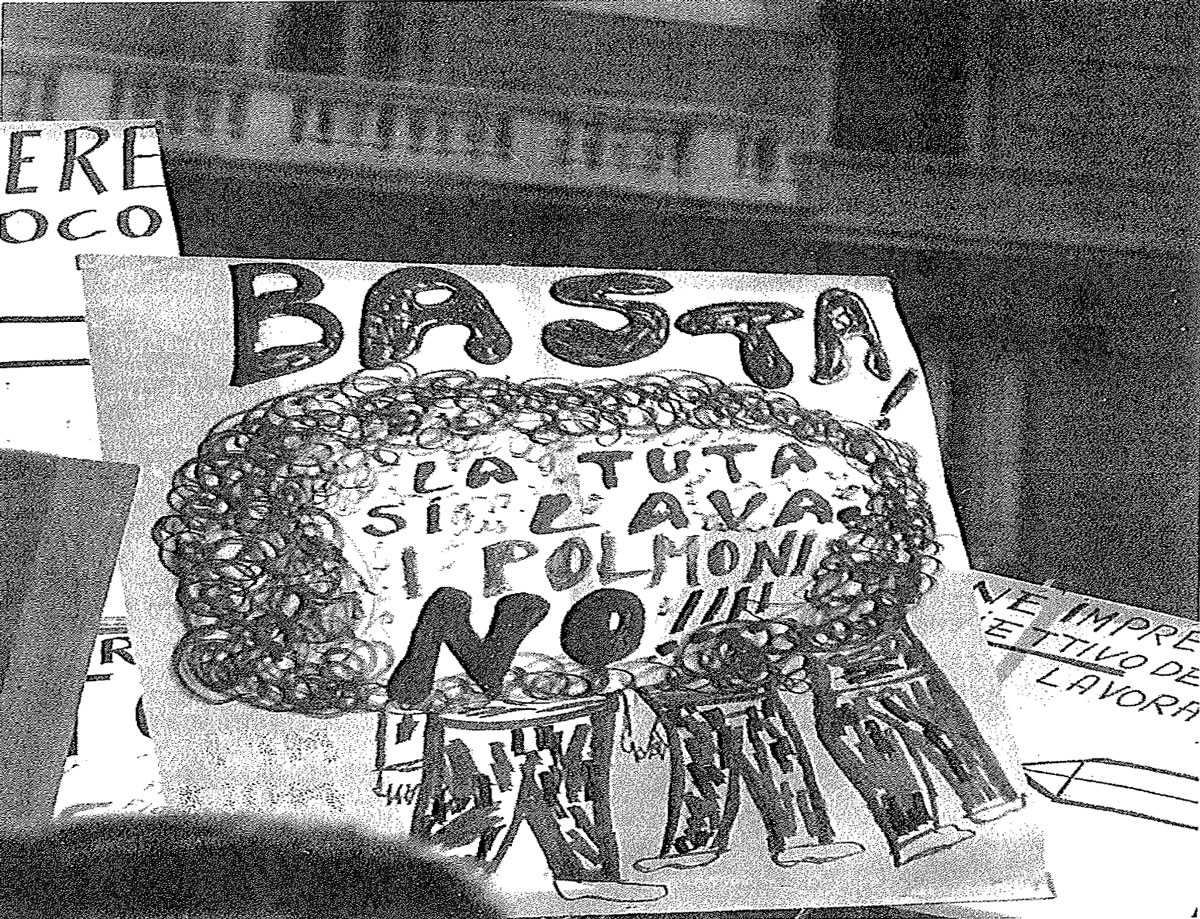

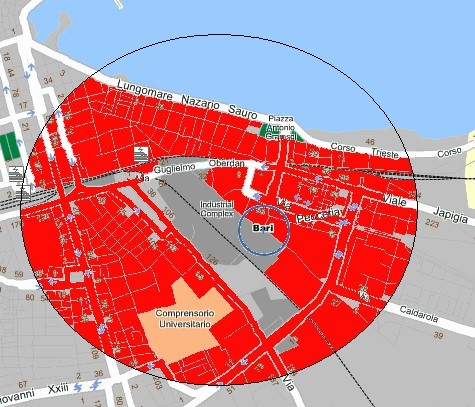

→ In 1972 workers obtained the intervention of the Ministry of Labour and the willingness of the City Council to set up an official investigation, which was also taken over by the Institute of Occupational Medicine. The studies carried out showed that the cases of pleural mesothelioma, while representing 1% of oncological illness, were particularly high among the workers and the inhabitants of the “red zone” which included the three neighbourhoods that were located within a linear kilometre area of the factory. This was followed in 1974 by a legal action against Fibronit, promoted by trade unions, patronages and 128 workers. And from that moment it became clear that health and environmental issues could no longer be ignored.

In 1985 Fibronit closed its doors due to a high health and environmental impact.

Investigations

Until the 70s there was no awareness of how dangerous asbestos fibers were. Workers were exposed to elevated fiber concentrations, mainly in the emptying and whisking sacks, grinding, turning and cutting phases.

It was only between the 60s and 70s, with full social struggles and protests against the damages caused by the industrialisation background, that a constantly growing debate on the consequences for the health of the workers in touch with asbestos arose. From the first observations, made in the 70s, concentrations of up to 20 ff/cc in the more critical areas had been discovered, in front of a limit of the work exposure of the Acgih (Association Advancing Occupational and Environmental Health) of 5 ff/cc. →

→ The reclamation took place inside confinement tensile structures necessary to avoid the dispersion of asbestos fibres into the air and the completion of the reclamation was completed in 2018.

After twenty years of social commitment of the City Committee and environmental struggles, of which the emblematic protagonist was the municipal councillor for the environment of the City of Bari, Maria Maugeri, the start of the “Parco della Rinascita” project has finally come, for which the Municipality obtained 11 million euros from the PNRR funds, to which were added another three and a half million from the Region.

THE COMMITTEE

The closure of Fibronit did not lead to an immediate cessation of pollution. The factory had in fact become a dangerous open-air dump which caused, in addition to the death of 180 workers from direct exposure to asbestos, 700 deaths in the coming years, provoked by the release of residues in the environment. After the first fibre cement roofing interventions in 1992 and the seizure of the area in 1995, the Fibronit City Committee was born in 1997.

Its objectives were to make the area safe and unbuildable, as well as to convert the factory into a park (“Parco della Rinascita” = “Park of Rebirth”). But only between 2005 and 2007 was an emergency safety measure carried out. After the block in 2011 due to the appeal to the Tar by the companies participating in the tender for the definitive safety works, in October 2016 the demolition operations of the sheds were started. →

→ The “ex Bricorama” building is also part of the areas subject to conversion, where it is expected to be able to place a further series of cultural, museum and/or commemorative functions.

Areas not accessible to citizens will also be circumscribed, on which monitoring will be carried out to verify the presence of any residues of volatile asbestos substances in the atmosphere.

THE RECONVERSION

The reconversion project of the area into an Urban Park was conceived through a participatory discussion of the Administration with the social partnership, associations and the world of schools, whose needs and proposals have provided useful indications for an initial re-functionalization of the park. The entire area covers 43 thousand and 385 square meters on which spaces for children, concert areas, green areas, areas for dogs, spaces for sports, social gardens will be created.

A complex intervention is also planned for the accessibility of the site and the connection with the urban fabric that provides for cycle-pedestrian roads and a bridge to cross the Bari-Taranto railway tracks and connect the park with via Amendola. →

Fibronit: demolition and reconversion work

Accounts

18 April, 1974: the day we entered Fibronit.

It was a relatively mild but not-yet-springlike afternoon. Entering via Caldarola was like entering a sort of concentration camp. Beyond the boundary walls: the city, the traffic, life. On this side: grey, anonymous and lager-like warehouses. Everything was still and motionless, both because the workers had stopped operations for months and because they had called a general strike in view of the court hearing. It seemed that everything had been abandoned for some time. Besides, sensing the possibility of an inspection, the management had ordered extraordinary and urgent cleaning which had made the working environments as aseptic as possible. The workers, the lawyers and the magistrate himself moved about in this motionless and moon-like landscape without perceiving what was hidden in this unreal world. Then, suddenly, almost at the end of the visit, a worker, shouting disconnected phrases in dialect, broke the wall of silence. He approached what looked like the mangers of a stable and began to stir with his hands what was contained in the wooden canals, in which a row of stirrers was still at that moment. He showed us how cement was mixed with asbestos when, as often happened, the automatic machinery didn’t work and the staff had to do the work by hand because the production cycle should not be interrupted. He bent his head into the trough, breathing in deeply the dust that was forming. Immediately, another worker got on a forklift and began to go around the courtyard, skidding and lifting asbestos and cement dust that quickly became a white cloud that enveloped us all. On that April day, Bari became aware of the permanent bomb it had within its walls. A bomb that had already caused hundreds of deaths and would continue to cause more.

Niccolò Muciaccia, 1974

Labour lawyer and district councillor in Bari

Testimonianze

Quando nella ‘zona rossa’ respiravamo il vento di morte

Era soltanto una fila di capannoni grigi, con le pareti alte simili a quelle delle rimesse per autotreni, le facciate pentagonali incutevano nell’ aria quell’ idea di perfezione geometrica, senso dello spazio post-moderno e “architettura della rinnovazione”. Lungo il corso del tempo si erano fatte consistenti le misteriose morti per asbestosi e mesotelioma pleurico. Cadevano come mosche. Prima una manciata di persone, un caso raro, ma poi quella manciata divenne una dozzina e poi divennero centinaia. Il mostro di pentagoni e calcestruzzo si stagliava sulla cortina di una strada vuota, che dopo le sette di sera in inverno diventava la pista di bulli e pazzi scatenati.[…]Ma quella fabbrica morì prima di tante altre morti strane e misteriose. Crisi economica, fine del ciclo produttivo, inutilità delle risorse, nuove prospettive di mercato, procedimento fallimentare, liquidatore e altre parole difficili. La fabbrica produceva cemento amianto, pulsava in quel centro periferico della città come una sanguisuga agonizzante. Succhiava sangue e restituiva vuoto mortifero. Ma la fabbrica morta non cessò di inquinare, anzi da morta divenne ulteriormente pericolosa e mortale. […] Per quei stranissimi anni universitari ho vissuto in piena “zona rossa” senza mai sapere nulla, senza sospettare che razza di bomba era innescata a pochi metri da dove vivevo. [..]Di tutto questo tanta gente sapeva pochissimo, i media erano ancora cauti nonostante quella fabbrica avesse chiuso i battenti nel 1986. I politici ancora di più. Qualcuno ha parlato di clima omertoso per l’emergenza amianto a Bari.[..] Poi vennero i giornali […] Iniziarono le inchieste della magistratura (e oggi le prime condanne), iniziai a sentir parlare del cisplatino, della gente che lo usava anche a Bari come a Taranto. Che quella era resistenza, senza vittorie per adesso, ma sempre resistere.

Mario Desiati da “La repubblica” del 9 luglio 2004